Interview with Kerstin Frödin and Åsa Unander-Scharin

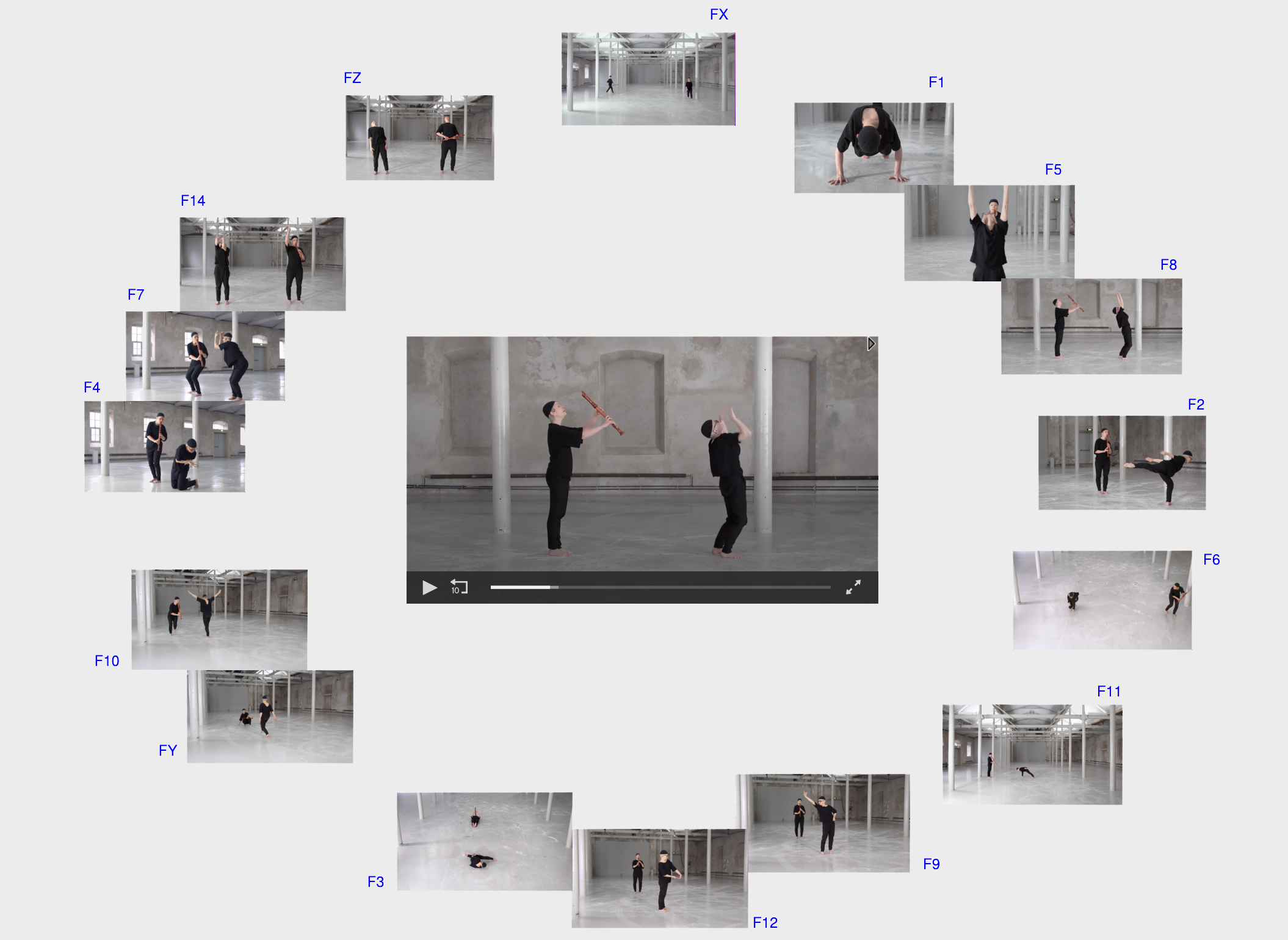

Still from Fragmente2 by Kerstin Frödin and Åsa Unander-Scharin.

The Society for Artistic Research’s RC Prize for Best Exposition was awarded this year to Fragmente2, a choreomusical project by musician Kerstin Frödin and choreographer-dancer Åsa Unander-Scharin.

Their collaborative work takes Makoto Shinohara’s composition Fragmente (1968) as its point of departure, expanding it into a contrapuntal dialogue between music and dance where both forms are treated as equal partners. In Fragmente2, sound and movement are explored as interwoven materials, not merely coexisting but actively shaping one another.

The project draws on experimental phenomenology and perspective variation, metaphorical mapping, and choreomusicology, using methods such as annotated scores, choreography scripts, video analysis, and metaphorical frameworks to articulate complex relationships between gesture, rhythm, and sound. What emerges is a performance structured as 17 fragments, where both performers are fully choreographed and engaged in a layered interplay of musical and choreographic “objects.”

At once rigorous and playful, in Fragmente2, artistic research serves as both method and outcome where the development, staging, and refinement of the choreomusical work, generate knowledge about how dance and music can function as equal, contrapuntal partners.

In this interview, Frödin and Unander-Scharin reflect on their creative process, their collaboration, and the artistic methods that underpin their research.

To start off, could you share a bit about how Fragmente2 first came about?

Kerstin:

Sure - I can start by talking about the music we’ve been working with, which is a contemporary classical piece for tenor recorder, written by Makoto Shinohara in 1968. It’s one of those pieces that many (many!) recorder players go through. I’ve lived with this piece since college. Many years ago, we created an initial version of it, and we found the music very enjoyable to explore, especially in relation to dance.

The music is very flexible—written as a set of short fragments that can be combined in different orders. You can decide that order before the performance or even during it, if you're playing solo. I’ve made many different versions of it over the years.

I remember Åsa and I first performed it in the early 2000s—maybe even earlier?

Åsa:

Yes, we performed it at the Dance Museum, the concert hall in Växjö, Vilnius (Lithuania) and Pusterviksteatern in Gothenburg. That must have been in 1998 or something like that.

Kerstin:

So even earlier than I remembered. We created a version and performed it a couple of times - later, when I started my PhD at Luleå University of Technology, we met again and were sort of reunited with this piece. It was such a lovely encounter and piece to revisit.

In relation to my PhD project, I was particularly interested in the role of the body in performing music.

Åsa:

In many earlier versions, Kerstin didn’t move. She played with the music stand in front of her, reading the score, while I danced. Of course, we had some contact on stage, but she wasn’t choreographed.

To me, the music feels incredibly gestural—it talks to me and makes me move. It’s a very interesting relationship, because it has these different impulses that feel a bit like talking. There’s a conversational quality, which I found very compelling to work with.

Each fragment is so different. It really opened up a lot of movement possibilities.

Kerstin:

There’s no fixed meter in the piece, so we could really play with timing—musically and physically. The music itself invites gestures. The piece allows new elements to come in because it’s already very gestural in its structure.

Åsa:

And it allowed for real dialogue. I could wait, move, and then Kerstin would play a small part of a fragment in response. It really encourages that kind of dialogue.

Was that first sense of the music—as conversational or gestural—part of what drew you into collaborating using this piece?

Kerstin:

Absolutely. The piece is quite short—only about seven or eight minutes—but every time we returned to it, we discovered something new and felt something new.

As Åsa said, in the beginning I played not by heart, but after spending so much time with Åsa and seeing how she works with movement, I suddenly felt that I also wanted to move and interact with her on the stage! So that was a new kick for us. That led to us creating a completely new version, which we eventually presented in the Research Catalogue.

How did it change your collaboration when Kerstin started moving as well?

Kerstin:

It was an interesting journey where we began to work with a metaphorical mapping of how we meet the choreographer, the dancer and the musician. We started to work out sceneries for each of the fragments—metaphoric sceneries—that I could also enter. Some of them I think Åsa already had in her mind, but we hadn’t shared them before in this way.

Now we had to share the idea: What kind of environment are we in during this scene? Are we animals? These scenes really switch from one thing to a completely different thing. And it helped us—and it helped me as a musician—to enter this kind of experience. An embodied experience.

Åsa:

My experience during the performance is that I “play” Kerstin and then she plays me. It’s a bit like a mechatronic robot or toy—that I play her and she plays me.

Do you think that being able to work like this—having that connection with the piece together on and off since 1998—gave you freedom to go beyond just using the score and really “play” each other as dancer/choreographer and musician?

Åsa:

Yes, definitely. It's like learning a poem by heart. Once you know it, you can recite it in many ways and bring out different interpretations. That’s similar to how we approached both the choreography and the music. Since we know it so well, we can play with it—and we also trust that the other person will understand what we’re doing.

Kerstin:

One of our main ideas was to act on equal terms, so we really approached this as two figures who play together.

Åsa:

We also had to find points in the piece where we could stretch time and where we couldn’t. Sometimes the movement has its own momentum and needs to continue and Kerstin had to know that.

In some moments we can meet and stretch time, for example, Kerstin might need air to play a phrase, or I might not be able to hold a pose—so there are practical, physical limits. To play with time like that, we had to know each other’s parts and how they worked in the body and with the instrument.

Kerstin:

Exactly. I write about this in my thesis as well. My experience in Fragmente2, which is a similar experience to working with chamber music, is that you are two equal players who know not only your own part, but the full score.

Although we follow a score and have a structure for what’s going to happen, we can stretch it and play within that.

Åsa:

I’ve worked a lot with robotics too—programming robots to move and perform gestures in relation to music - and sometimes also in this piece, it feels like that.

The music can sound like musique concrète—where you record and manipulate sounds, play them backwards, or stretch them. Even though this is analog, played live on the recorder, it has that same quality.

And the movements too, they are somehow movements concrète. It’s not like we tell a story. It’s more like fragments of gestures that we turn back and forth and reassemble. In that way, the choreography mirrors the structure of the music.

Figure 2: Kerstin Frödin and Åsa Unander-Scharin in the exhibition space Färgfabriken, Stockholm, 2021. Photo credit: Patrik Eriksson

You’d been working with this piece for many years before bringing it into the Research Catalogue. Was the RC something you had in mind from the start, or did that come later?

Kerstin:

Initially, we just worked on it as part of my artistic PhD and as an artistic exploration. But later, when we structured the exposition in columns on the Research Catalogue, we saw that it was the perfect platform actually to present the work because it allowed us to show video, stills, sound, and text all in one place.

Åsa:

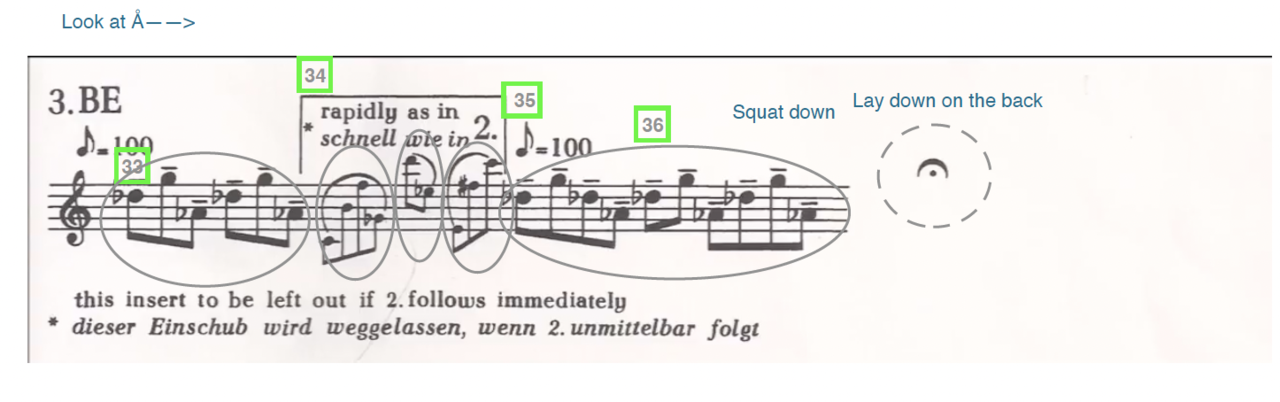

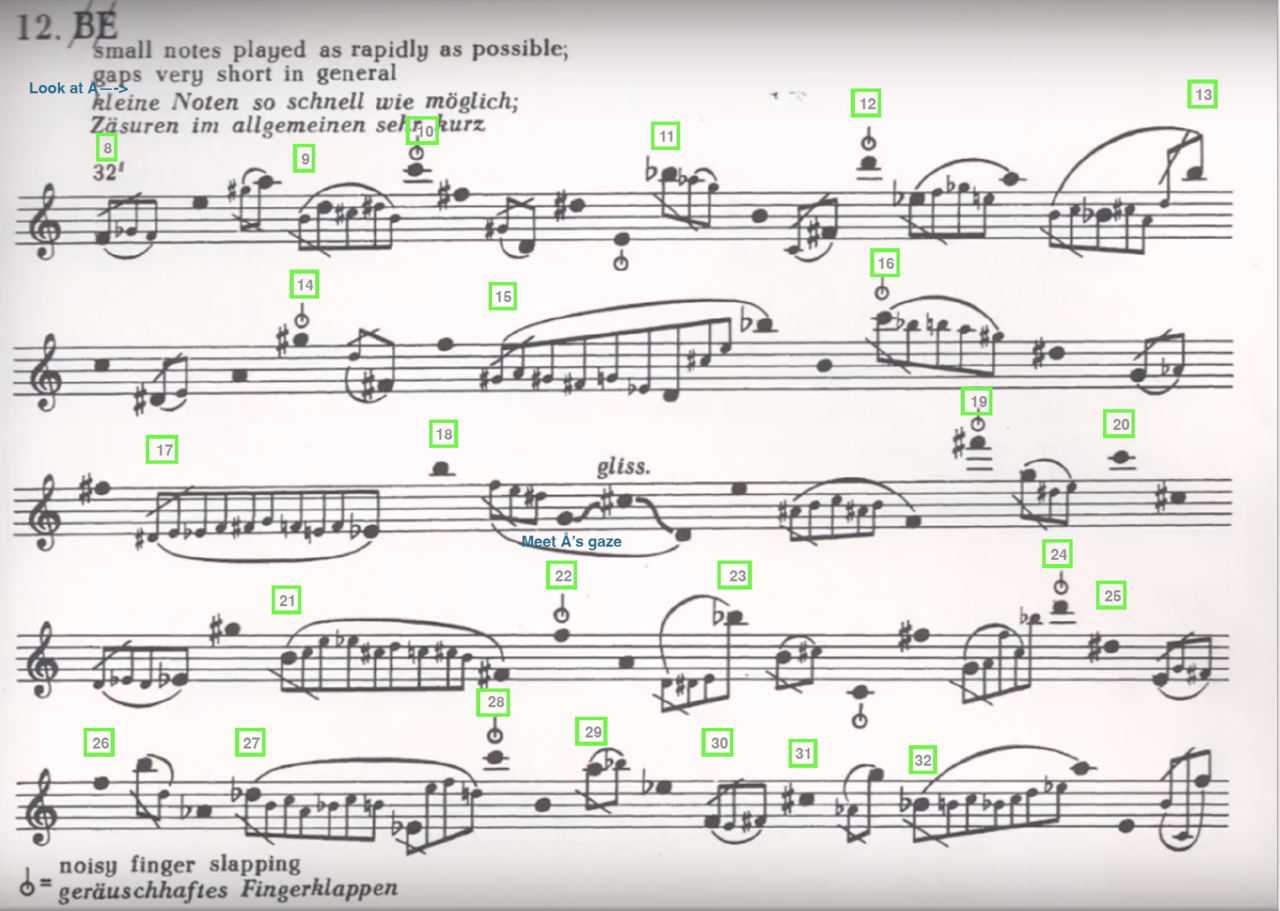

We had already made annotations in the score while we worked on the piece, but for the exposition, we had to make those annotations understandable to others.

In order to compose the work we already needed that kind of material.

Kerstin:

The opening page of the exposition—with the circle— is very close to the actual choreography itself. That circle is central to the piece and the design of the exposition is very close to the structure of the performance.

Did turning the piece into an exposition with text, stills and video for the RC change anything for you? Or did it change the piece itself?

Kerstin:

Not the piece itself. But the process of writing about it, explaining it, and organising it gave us new insight. It’s another journey. I learned a lot from the artistic process when creating the exposition. It became clearer how everything was connected - you see, ‘oh this was like this because of this’ and you can see a red thread, an artistic thread, throughout the long journey we had with this work.

How long did it actually take to put the exposition together?

Kerstin:

Oh, several months. But we’ve been collecting the material for years, and then we had to choose and organise it.

So could you say that creating the exposition became a kind of reflection period for you?

Kerstin:

Yes, absolutely.

Since our exposition was published in the Ruukku journal, we also received useful feedback from the peer review and jury.

How do you see the relationship between the artistic research side of this project and the performance itself?

Åsa:

We found that in order to create the piece, we had to do this kind of phenomenological perspective variation. That’s really the artistic process. The process, the phenomenological variation, it's already there - even if we wouldn't have called it artistic research, it's in the artistic work.

Kerstin:

Yes, I agree.

And as soon as you start presenting the work—giving seminars, writing about it, making this exposition, structuring it for others—it becomes even more clear. It becomes something that others can use in the future and continue to work with. Hopefully, it can also inspire others to explore similar directions.

Are you planning to do more with Fragmente2, or is the work now more feeding into other projects that you’re doing together?

Åsa:

It’s already fed into other projects, but I wouldn’t rule out performing it again. If we do, I’m sure it will become something new again.

Kerstin:

Yes, each time we revisit the piece, we learn something new from it and develop something new. What you see in the video is just one possible version. This work has already gone into another piece that we did together with several other artists, ‘Conference of the Birds’, which was also part of my PhD project.

Even if we go on to do different things, we have this rather unique experience.

Working so closely across art forms has been incredibly rewarding.

Do you both often collaborate across disciplines, or is this particular collaboration the main one between music and dance for you?

Åsa:

As a choreographer, I collaborate all the time—with composers, dancers, opera singers, robotics, science and so on.

Kerstin:

Same for me. I do a lot of interdisciplinary work—in staged performances, opera, chamber music. It’s a wonderful field with endless possibilities.

So maybe I should have asked—do you ever do solo work?

Åsa:

I do solo work too, but even then, there’s usually music involved. I’ve developed interactive digital music instruments, so I play music with my body which also makes the music live and interactive. I discovered many years ago that I don’t want to dance to pre-recorded/playback music. That’s not my thing. I want to play. I want to dance with live music. So that could be the live, interactive digital instruments, but also, of course, live musicians.

Dancing to recorded playback music… It's like it's dead for me. I prefer it when I have to be very sensitive to what's happening in the music, and if it's recorded music, then it will perform exactly the same every time. I then become more of a machine rather than someone really attentive to the music.

Yeah, so then you don’t feel the presence of another person in the room. Even if that “other” is the music itself?

Åsa:

Exactly. Or the presence of the music I create.

Stills from Fragmente2 by Kerstin Frödin and Åsa Unander-Scharin.

You ended up submitting Fragmente2 to the RC Prize and winning. What made you decide to submit it? Was that your intention all along?

Kerstin:

No, not really. We were just happy with our exposition and wanted to share it more widely.

Åsa:

As a member of SAR, I received the open call to submit expositions. We submitted it and then we forgot about it! So winning was a really happy surprise.

What kind of response have you had since winning the prize?

Kerstin:

It’s definitely brought more attention to the work. When there’s a spotlight on the exposition like this, obviously more people see it.

Åsa:

I’m also a professor of Music Performance at Luleå University of Technology in northern Sweden. I’ll definitely use the exposition to show my students how artistic research can be presented through the Research Catalogue. Winning the prize makes it clearer how this can work for others too. Other PhD students at the university are also interested in how we worked, how we thought about the exposition and so on.

Do you see the exposition more as documentation of the piece, or as a work of art in its own right?

Åsa:

It’s both. Of course, it’s an archive of the work and the process, but since the live performance was a physical experience in space, and this is a recorded and edited version, it becomes a new version—an artistic work in itself.

Kerstin:

And because of all the explanations and background we’ve included—the additional pages and layers in the exposition—it adds even more context. It sets it in relation to so much more and opens it up.

It’s really useful and inspiring for others.

We were asked during another presentation whether someone else could recreate exactly what we did and that question surprised us a bit. We never thought of that!

As Åsa said, much work that is done today between music and performance uses pre-recorded music and, as she said, that doesn’t feel as lively as it should be. It’s dead in some parts, because you can’t reach this interaction. I hope the exposition can inspire more people to work in this deeply interactive way. In that sense, you can say the exposition is a piece of art because it presents something that lives its own life, I think.

Åsa:

Our idea was also that the audience could surround us—in a circle—during the live performance. But of course, a video only gives one angle at a time. Still, the exposition lets people enter the work in different ways.

Right. That’s interesting—because when people encounter the exposition at home, they might explore it in fragments over time, almost like a resource they can return to at their own pace.

They might watch a bit and then get up to do something else, but then return to it later. You can explore it slowly.

Kerstin:

Exactly. With the exposition you can stop at one fragment and go into it, you can open it. In a way, the exposition is like a Christmas calendar. You can open a door and see what kind of metaphor it was built on and what kind of interaction we see here.

It gives several dimensions to the piece that we, as the artists, know are there, but to the viewer are new access points you don’t get when you just go to the performance.

The exposition transfers new types of knowledge that can’t be reached in a live performance, but then there you get something else.

Still from Fragmente2 by Kerstin Frödin and Åsa Unander-Scharin.

Yes, so there’s a trade-off, right? A live performance might feel more immersive, but with the exposition you have the opportunity to read, pause and understand much more about the piece and its background.

Kerstin

In a way, it's a huge exposition—it contains a lot of material and it needs time. It’s not something you can just skim in 15 minutes. But I think it’s worth revisiting it and as you said, come back to it several times.

Åsa:

And when we perform, there are so many things we don’t write down. When we created the exposition we realised just how much there is than what we have included.

Every breath, every gesture.

Still, because the piece is only about 8 minutes long, it was possible to capture and explain a lot.

But of course, it’s not everything. It never can be. But I do think it’s enough for people to understand the essence.